In 1986, the US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the June sucker as an endangered species. Found only in Utah Lake, the fish had the ominous distinction of being the first endangered species listed along the Wasatch Front. The listing was inevitable.

For over a century, Utah Lake and its native fish species had been in decline. Fishery managers had few options. Stunted white bass, seasonal runs of walleye, and the occasionally good catch of catfish couldn’t change the dominating carp populations. The remaining June suckers were old, dying, and not being replaced. Wastes from the cities and towns were often dumped into the lake and its tributaries. And the clean water from surrounding mountains was stored and diverted before it could reach the lake. June sucker and the ecosystem on which they depended were on the ropes.

The Issue

Resource managers didn’t fully comprehend what changes the endangered listing would bring, and outside of early captive breeding efforts, not much changed in terms of management of the lake and its tributaries.

In the early 1990s, the situation started to change. Water users saw the listing as a significant impediment to development of the Central Utah Project. Biologists charged with saving the fish knew they had little time or the fish would be gone. Confrontation was almost certain when more water needed to be developed for human use and the status of the fish was precipitously declining.

The answer: Cooperation.

Get along, cooperate, and develop a program to make sure water use continued and the fish would be saved.

The Work

In April 2002, a program (June Sucker Recovery Implementation Program – JSRIP) was finalized, biologists and water developers came together. Utah county commissioners, mayors, and local leaders saw the need and value in saving Utah Lake, although the next step forward wasn’t clear. Dealing with a sucker population of less than 500 adults, the JSRIP began implementing recovery actions through an adaptive management approach. The approach focused on improving the Utah Lake ecosystem, not just increasing June sucker numbers. The projects were wide ranging:

- Utah Lake carp removal

- Securing water for instream flows in the Provo River and Hobble Creek

- Habitat restoration on Hobble Creeek

- Building a new fish hatchery

- Researching Utah Lake and the fish community

- Producing a Utah Lake documentary

The Comeback

After 18 years of such efforts, in the fall of 2019, the JSRIP got welcome news that the US Fish and Wildlife Service had proposed downlisting the June sucker from endangered to threatened status. While only a proposal at this point, the JSRIP is anxiously awaiting the final determination. The status change is a rare accomplishment, as only four other fish have reached this point in recovery.

June sucker have come back from the brink of extinction, even in the face of increasing threats to the lake. The effectiveness of the JSRIP means that water use, recreational activities, and commercial development has been able to proceed despite the presence of an endangered species.

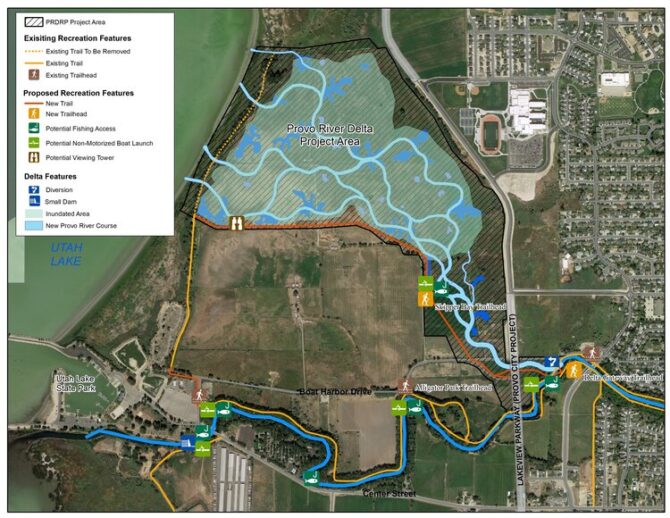

This spring, the JSRIP has implemented its largest habitat restoration project, the Provo River Delta Restoration. This project will restore the connection between the Provo River and Utah Lake and create the habitat conditions necessary to support all June sucker life stages. But it will also bring so much more. It will provide new access to Utah Lake, additional trails and trailheads, a new community park, and a delta wetland that will help improve water quality. The construction will take several years, but the project represents a transition as June sucker recovery moves forward.

The Takeaway

The JSRIP will continue to implement recovery actions, make sure progress toward recovery continues, and work to improve Utah Lake. So why should we care about some endangered sucker fish? The Endangered Species Act can be an 800-pound gorilla. Whether we like the law or not, it requires opposing sides to address issues related to the health of a species and the ecosystem on which it depends.

Fortunately, sides can cooperate as easily as they can litigate. We have found that cooperation is the key to success. Simply, without the June sucker, there would be no water back in tributaries, no habitat restoration, no expansion of hatcheries, no monitoring of the Utah Lake fish community, and a decline in resources available to make Utah Lake a better place…for everything and everyone that uses it.